Unit 13

Bac

Exam file

Préparation aux évaluations communes

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Évaluations communes

1H30Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Compréhension de l'oral Ruby Bridges Visits the President

1

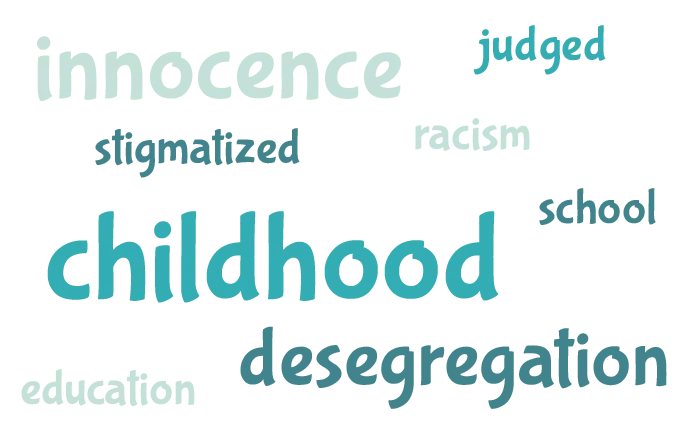

Avant l'écoute Lisez le titre ci-dessus et regardez le nuage de mots

a. Sur quoi peut porter cet enregistrement ? Faites trois hypothèses.

b. Trouvez cinq autres mots que vous pourriez entendre dans l'enregistrement.

2

Après l'écoute En rendant compte, en français, du document, vous montrerez que vous avez compris les éléments suivants :

- Le thème principal du document ;

- À qui s'adresse le document ;

- Le déroulement des faits, la situation, les événements, les informations ;

- L'identité des personnes ou des personnages et, éventuellement, les liens entre elles / entre eux ;

- Les éventuels différents points de vue ;

- Les éventuels éléments implicites du document ;

- La fonction et la portée du document (relater, informer, convaincre, critiquer, dénoncer, etc.).

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Ruby Bridges visits with the President and her portrait, 2011.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Expression écrite

Sujet A - Texte

“Freeing yourself was one thing, claiming ownership of that freed self was another.” Discuss this quote by Toni Morrison in the light of her life and work.

Sujet B - Texte, vidéo

How is art used to empower black communities, promote social justice and spread a message of hope?

Sujet C - Vidéo

React to the video and comment on Obama's quote: “If it had not been for you guys, I might not be here and we would not be looking at this together.”

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

- Assurez-vous de faire la différence entre faits objectifs et opinions personnelles.

- Donnez votre opinion et argumentez (justifiez avec des exemples et des idées personnelles).

- Structurez votre réponse en utilisant des mots de liaison.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Compréhension de l'écrit

Of all the mantles that have been foisted on Toni Morrison's shoulders, the heaviest has to be “the conscience of America”. It's both absurd-sounding and true. For almost half a century her subject has been racial prejudice in the United States, a story that she has told and retold with a steadiness of rage and compassion. Her latest novel, God Help the Child, is her 11th. [...]

Morrison turned 84 in February. Her many literary laurels include a Pulitzer in 1988 for Beloved, a Nobel in 1993, and, in 2012, the presidential medal of freedom, from her friend Barack Obama. [...]

Bride's blackness is both the source of her childhood misery – her lighter-skinned mother is so horrified by it that she considers killing her baby – and of her adult success. She works in the fashion and beauty industry where, heeding one stylist's dictum to dress only in white, she makes herself, “a panther in snow”, an exoticised “other”. The novel intimates that fetishising blackness, both for the observer and the observed, might be just as insidious as outright prejudice. There's the ex-boyfriend, for example, who seems to claim her as some kind of racial trophy. When this young white man takes her home to his parents it's clear “that I was there to terrorise his family, a means of threat to this nice old white couple. ‘Isn't she beautiful?' he kept repeating ... His eyes were gleaming with malice.”

“I'm trying to say,” Morrison tells me now, “it's just a colour.” [...]

[She] began her publishing career 45 years ago. She has always talked about her first novel with disarming simplicity: it was the book she wanted to read and that did not exist. So, as a single working mother of two small sons, she rose at 4am every day and wrote it. Published in 1970, The Bluest Eye is the story of Pecola Breedlove, a young black girl who prays for blue eyes. Morrison wrote in a 2007 foreword that she wanted to focus “on how something as grotesque as the demonisation of an entire race could take root inside the most delicate member of society: a child; the most vulnerable member: a female”.

Most writers claim to abhor labels but Morrison has always welcomed the term “black writer”. “I'm writing for black people,” she says, “in the same way that Tolstoy was not writing for me, a 14-year-old coloured girl from Lorain, Ohio. I don't have to apologise or consider myself limited because I don't [write about white people] – which is not absolutely true, there are lots of white people in my books. The point is not having the white critic sit on your shoulder and approve it” – she refers to the writer James Baldwin talking about “a little white man deep inside of all of us”. Did she exorcise hers? “Well I never really had it. I just never did.”

[...] It was this self-assurance, too, that gave her the courage to split from her husband when she was pregnant with her second child and, that made her such an iconoclastic force as an editor at Random House where she propelled works by black writers such as Angela Davis and Toni Cade Bambara into the mainstream. Finally, of course, she herself became one of the publishing house's most cherished names.

Morrison turned 84 in February. Her many literary laurels include a Pulitzer in 1988 for Beloved, a Nobel in 1993, and, in 2012, the presidential medal of freedom, from her friend Barack Obama. [...]

Bride's blackness is both the source of her childhood misery – her lighter-skinned mother is so horrified by it that she considers killing her baby – and of her adult success. She works in the fashion and beauty industry where, heeding one stylist's dictum to dress only in white, she makes herself, “a panther in snow”, an exoticised “other”. The novel intimates that fetishising blackness, both for the observer and the observed, might be just as insidious as outright prejudice. There's the ex-boyfriend, for example, who seems to claim her as some kind of racial trophy. When this young white man takes her home to his parents it's clear “that I was there to terrorise his family, a means of threat to this nice old white couple. ‘Isn't she beautiful?' he kept repeating ... His eyes were gleaming with malice.”

“I'm trying to say,” Morrison tells me now, “it's just a colour.” [...]

[She] began her publishing career 45 years ago. She has always talked about her first novel with disarming simplicity: it was the book she wanted to read and that did not exist. So, as a single working mother of two small sons, she rose at 4am every day and wrote it. Published in 1970, The Bluest Eye is the story of Pecola Breedlove, a young black girl who prays for blue eyes. Morrison wrote in a 2007 foreword that she wanted to focus “on how something as grotesque as the demonisation of an entire race could take root inside the most delicate member of society: a child; the most vulnerable member: a female”.

Most writers claim to abhor labels but Morrison has always welcomed the term “black writer”. “I'm writing for black people,” she says, “in the same way that Tolstoy was not writing for me, a 14-year-old coloured girl from Lorain, Ohio. I don't have to apologise or consider myself limited because I don't [write about white people] – which is not absolutely true, there are lots of white people in my books. The point is not having the white critic sit on your shoulder and approve it” – she refers to the writer James Baldwin talking about “a little white man deep inside of all of us”. Did she exorcise hers? “Well I never really had it. I just never did.”

[...] It was this self-assurance, too, that gave her the courage to split from her husband when she was pregnant with her second child and, that made her such an iconoclastic force as an editor at Random House where she propelled works by black writers such as Angela Davis and Toni Cade Bambara into the mainstream. Finally, of course, she herself became one of the publishing house's most cherished names.

Toni Morrison: ‘I'm writing for black people ... I don't have to apologise'

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Questions

a) Pick out as many elements as you can to make a brief presentation about Toni Morrison.

b) What sort of recognition did she receive in her lifetime?

c) List the expressions used to refer to black people in paragraph 3? Which stylistic devices are used? What is their purpose?

b) What sort of recognition did she receive in her lifetime?

c) List the expressions used to refer to black people in paragraph 3? Which stylistic devices are used? What is their purpose?

d) Rephrase the sentence in bold letters in your own words. What is implied?

e) True or False: Toni Morrison only writes about black people. Use a quote and justify in your own words.

f) How is Toni Morrison similar to or different from Ruby Bridges as an American icon?

e) True or False: Toni Morrison only writes about black people. Use a quote and justify in your own words.

f) How is Toni Morrison similar to or different from Ruby Bridges as an American icon?

Une erreur sur la page ? Une idée à proposer ?

Nos manuels sont collaboratifs, n'hésitez pas à nous en faire part.

j'ai une idée !

Oups, une coquille