Anglais 2de

Rejoignez la communauté !

Co-construisez les ressources dont vous avez besoin et partagez votre expertise pédagogique.

Mes Pages

Unité de transition collège/lycée

1 • Generations living together

Ch. 1

Food for joy, food for ploy

Ch. 2

No future? No way!

2 • Working worlds

Ch. 3

Working in Silicon Valley

Ch. 4

STEM women rock!

3 • Neighbourhoods, cities and villages

Ch. 5

Ticket to ride

Ch. 6

South Afri...cans

Ch. A

Dreaming city stories - Digital content only

Ch. num

Diners and Pubs

4 • Representation of self and relationships with others

Ch. 7

Fashion-able

Ch. 8

Look at me now!

Ch. B

Inking the future - Digital content only

5 • Sports and society

Ch. 9

Spirit in motion

Ch. 10

Athletic scholarship

6 • Creation and arts

Ch. 11

“You see but you don’t observe!”

Ch. 12

From silent to talkie

Ch. C

Copying or denouncing? - Digital content only

7 • Saving the planet, designing possible futures

Ch. 13

Young voices of change

Ch. 14

Biomimicry: a sustainable solution?

Ch. num

National Parks

8 • The past in the present

Ch. 15

Twisted tales

Ch. 16

The Royals

Ch. num

The Royals 2.0 "Family Business"

Ch. D

All Hallows' Eve - Digital content only

Ch. num

Spooky Scotland

Fiches méthode

Précis

Ch. 18

Précis culturel

Ch. 19

Précis de communication

Ch. 20

Précis phonologique

Ch. 21

Précis grammatical

Verbes irréguliers

Rabats

Révisions

Unit 8

Reading corner

A deadly portrait

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Text document

He went in quietly, locking the door behind him, as was his custom, and dragged1

the purple hanging from the portrait. A cry of pain and indignation broke from

him. He could see no change, save that in the eyes there was a look of cunning2

and

in the mouth the curved wrinkle of the hypocrite. The thing was still loathsome3

— more loathsome, if possible, than before — and the scarlet dew that spotted the

hand seemed brighter, and more like blood newly spilled. Then he trembled. Had it

been merely vanity that had made him do his one good deed? Or the desire for a new

sensation, as Lord Henry had hinted, with his mocking laugh? Or that passion to act

a part that sometimes makes us do things finer than we are ourselves? Or, perhaps, all

these? And why was the red stain larger than it had been? It seemed to have crept like

a horrible disease over the wrinkled fingers. There was blood on the painted feet, as

though the thing had dripped — blood even on the hand that had not held the knife.

Confess? Did it mean that he was to confess? To give himself up and be put to death?

He laughed. He felt that the idea was monstrous. Besides, even if he did confess, who

would believe him? There was no trace of the murdered man anywhere. Everything

belonging to him had been destroyed. He himself had burned what had been belowstairs. The world would simply say that he was mad. They would shut him up if he

persisted in his story… Yet it was his duty to confess, to suffer public shame, and to

make public atonement. There was a God who called upon men to tell their sins4

to

earth as well as to heaven. Nothing that he could do would cleanse him till he had told

his own sin. His sin? He shrugged his shoulders. The death of Basil Hallward seemed

very little to him. He was thinking of Hetty Merton. For it was an unjust mirror, this

mirror of his soul that he was looking at. Vanity? Curiosity? Hypocrisy? Had there

been nothing more in his renunciation than that? There had been something more.

At least he thought so. But who could tell?… No. There had been nothing more.

Through vanity he had spared her. In hypocrisy he had worn the mask of goodness.

For curiosity's sake he had tried the denial of self. He recognized that now.

But this murder—was it to dog him all his life? Was he always to be burdened by his past? Was he really to confess? Never. There was only one bit of evidence left against him. The picture itself— that was evidence. He would destroy it. Why had he kept it so long? Once it had given him pleasure to watch it changing and growing old. Of late he had felt no such pleasure. It had kept him awake at night. When he had been away, he had been filled with terror lest other eyes should look upon it. It had brought melancholy across his passions. Its mere memory had marred many moments of joy. It had been like conscience to him. Yes, it had been conscience. He would destroy it.

He looked round and saw the knife that had stabbed Basil Hallward. He had cleaned it many times, till there was no stain left upon it. It was bright, and glistened. As it had killed the painter, so it would kill the painter's work, and all that that meant. It would kill the past, and when that was dead, he would be free. It would kill this monstrous soul-life, and without its hideous warnings, he would be at peace. He seized the thing, and stabbed the picture with it.

There was a cry heard, and a crash. The cry was so horrible in its agony that the frightened servants woke and crept out of their rooms. Two gentlemen, who were passing in the square below, stopped and looked up at the great house. They walked on till they met a policeman and brought him back. The man rang the bell several times, but there was no answer.

Except for a light in one of the top windows, the house was all dark. After a time, he went away and stood in an adjoining portico and watched.

“Whose house is that, Constable?” asked the elder of the two gentlemen.

“Mr. Dorian Gray's, sir,” answered the policeman.

They looked at each other, as they walked away, and sneered. One of them was Sir Henry Ashton's uncle.

Inside, in the servants' part of the house, the half-clad domestics were talking in low whispers to each other. Old Mrs. Leaf was crying and wringing her hands. Francis was as pale as death.

After about a quarter of an hour, he got the coachman and one of the footmen and crept upstairs. They knocked, but there was no reply. They called out. Everything was still. Finally, after vainly trying to force the door, they got on the roof and dropped down on to the balcony. The windows yielded easily—their bolts were old.

When they entered, they found hanging upon the wall a splendid portrait of their master as they had last seen him, in all the wonder of his exquisite youth and beauty. Lying on the floor was a dead man, in evening dress, with a knife in his heart. He was withered, wrinkled, and loathsome of visage. It was not till they had examined the rings that they recognized who it was.

But this murder—was it to dog him all his life? Was he always to be burdened by his past? Was he really to confess? Never. There was only one bit of evidence left against him. The picture itself— that was evidence. He would destroy it. Why had he kept it so long? Once it had given him pleasure to watch it changing and growing old. Of late he had felt no such pleasure. It had kept him awake at night. When he had been away, he had been filled with terror lest other eyes should look upon it. It had brought melancholy across his passions. Its mere memory had marred many moments of joy. It had been like conscience to him. Yes, it had been conscience. He would destroy it.

He looked round and saw the knife that had stabbed Basil Hallward. He had cleaned it many times, till there was no stain left upon it. It was bright, and glistened. As it had killed the painter, so it would kill the painter's work, and all that that meant. It would kill the past, and when that was dead, he would be free. It would kill this monstrous soul-life, and without its hideous warnings, he would be at peace. He seized the thing, and stabbed the picture with it.

There was a cry heard, and a crash. The cry was so horrible in its agony that the frightened servants woke and crept out of their rooms. Two gentlemen, who were passing in the square below, stopped and looked up at the great house. They walked on till they met a policeman and brought him back. The man rang the bell several times, but there was no answer.

Except for a light in one of the top windows, the house was all dark. After a time, he went away and stood in an adjoining portico and watched.

“Whose house is that, Constable?” asked the elder of the two gentlemen.

“Mr. Dorian Gray's, sir,” answered the policeman.

They looked at each other, as they walked away, and sneered. One of them was Sir Henry Ashton's uncle.

Inside, in the servants' part of the house, the half-clad domestics were talking in low whispers to each other. Old Mrs. Leaf was crying and wringing her hands. Francis was as pale as death.

After about a quarter of an hour, he got the coachman and one of the footmen and crept upstairs. They knocked, but there was no reply. They called out. Everything was still. Finally, after vainly trying to force the door, they got on the roof and dropped down on to the balcony. The windows yielded easily—their bolts were old.

When they entered, they found hanging upon the wall a splendid portrait of their master as they had last seen him, in all the wonder of his exquisite youth and beauty. Lying on the floor was a dead man, in evening dress, with a knife in his heart. He was withered, wrinkled, and loathsome of visage. It was not till they had examined the rings that they recognized who it was.

1. pulled / took off 2. intelligence 3. disgusting 4. immoral acts

The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde, 1891.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Questions

a) What feelings

does Dorian Gray

experience upon

seeing his portrait?

b) How does the narrator describe the portrait through the eyes of Dorian Gray himself? Why? Focus on the words in bold letters for help.

c) Identify and list all the references to blood in the first paragraph

d) List the feelings and emotions presented in this paragraph.

b) How does the narrator describe the portrait through the eyes of Dorian Gray himself? Why? Focus on the words in bold letters for help.

c) Identify and list all the references to blood in the first paragraph

d) List the feelings and emotions presented in this paragraph.

e) What do you think

of Dorian's plan?

What is it?

f) Find three examples in the first three paragraphs showing that Dorian Gray is an evil man. Quote the text.

g) How do you understand and interpret the very end?

f) Find three examples in the first three paragraphs showing that Dorian Gray is an evil man. Quote the text.

g) How do you understand and interpret the very end?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

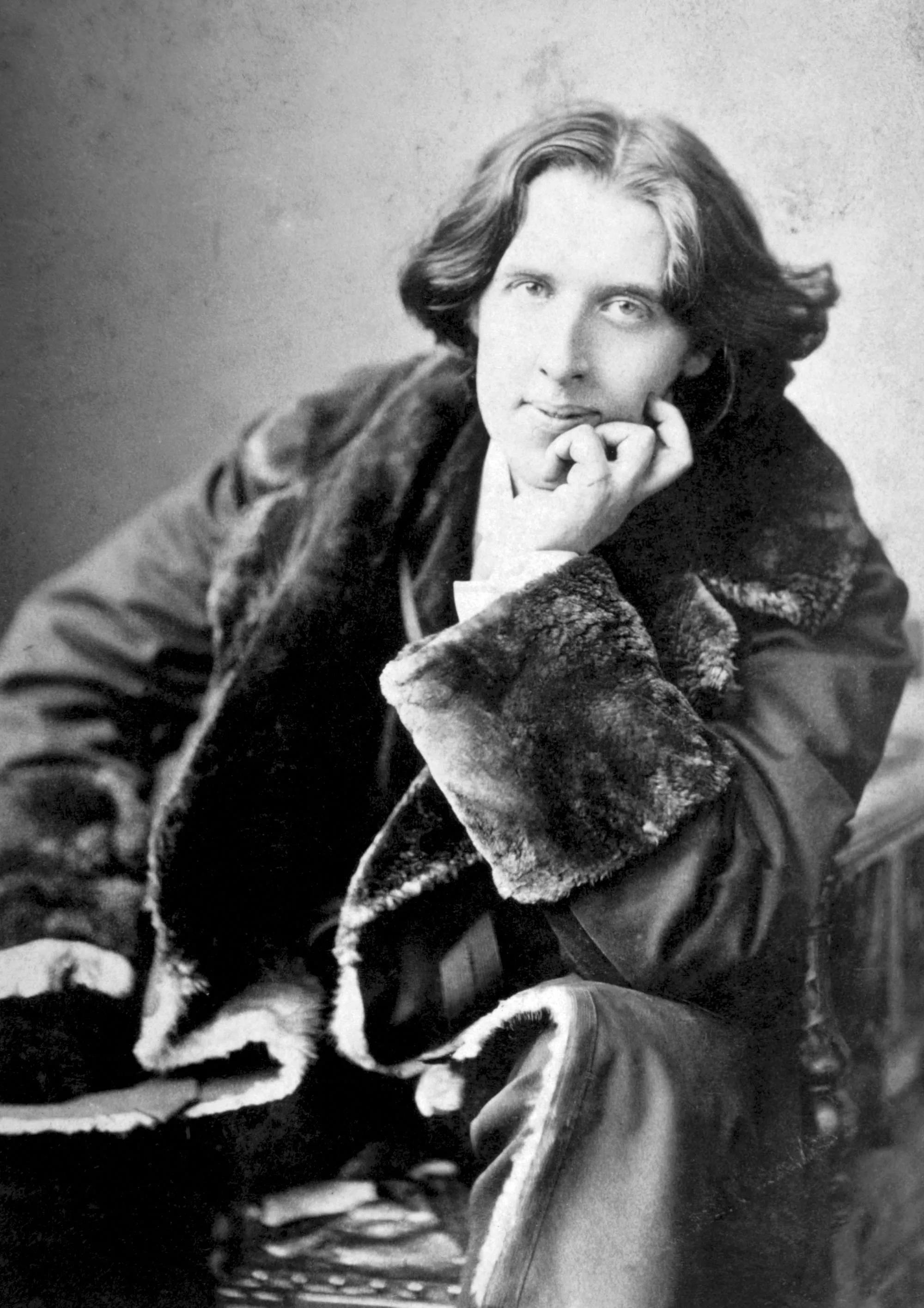

Oscar Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November

1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After

writing in different forms throughout the

1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s. He is best

remembered for his novel The Picture of

Dorian Gray, and the circumstances of his

imprisonment and early death.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Your time to shine!

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

To celebrate the 120-year anniversary of Oscar Wilde's death, people around the world pay tribute to his work. You participate by writing a sequel to Dorian Gray.

1. Imagine the servant's reaction and conversation

after discovering the body (180 words).

2. Write the synopsis of your own sequel to the novel (150 words).

2. Write the synopsis of your own sequel to the novel (150 words).

Enregistreur audio

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Une erreur sur la page ? Une idée à proposer ?

Nos manuels sont collaboratifs, n'hésitez pas à nous en faire part.

j'ai une idée !

Oups, une coquille